Music: Advanced Dynamic Music with Yihui Liu

University of California, Irvine | April 14, 2022

Yihui Liu is a composer, music producer, songwriter, classical pianist, and educator. She has been professionally trained in music for over 20 years. Holding a bachelor’s degree from the Oberlin Conservatory as well as a master’s degree from the Juilliard School, she is currently researching her doctoral thesis about composing deep adaptive music for video games at the ICIT program at UC Irvine. Her recent academic writing includes a paper about adaptive game music published at the Alliance of Women in Media Arts and Technology Conference (AWMAT) 2019. For more information on Liu's research, please view her presentation in the November 2020 CTSA Graduate Research Colloquium here and visit her website: https://www.melismaticwitch.com/.

Jesse Colin Jackson (JCJ): Can you tell us about your current graduate research at UC Irvine?

Yihui Liu (YL): My research is about composing dynamic music for video games. For my thesis, I am researching algorithmic composition because video games are such an interactive medium. I found that algorithmic composition in contemporary classical music or any genre of music can suit this medium really well.

JCJ: Wow, that makes immediate sense to me. And you are a Ph.D. student in the Integrated Composition, Improvisation, and Theory (ICIT) program in the Music department?

YL: Yes, so many people have been asking about what's ICIT.

JCJ: I think the ICIT program, which started as an M.F.A. and became a Ph.D., is symptomatic of the problem of research in the arts. You're trying to take a whole bunch of things that are both interdisciplinary and different across the arts to other disciplines, and put them in one basket. The program takes in five students a year, so your cohort is going to be unique. You'll all be so different from each other relative to other schools. But it's such a great program and a good model for the other departments. Your idea would allow the music to proceed in more direct response to whatever the character playing is doing?

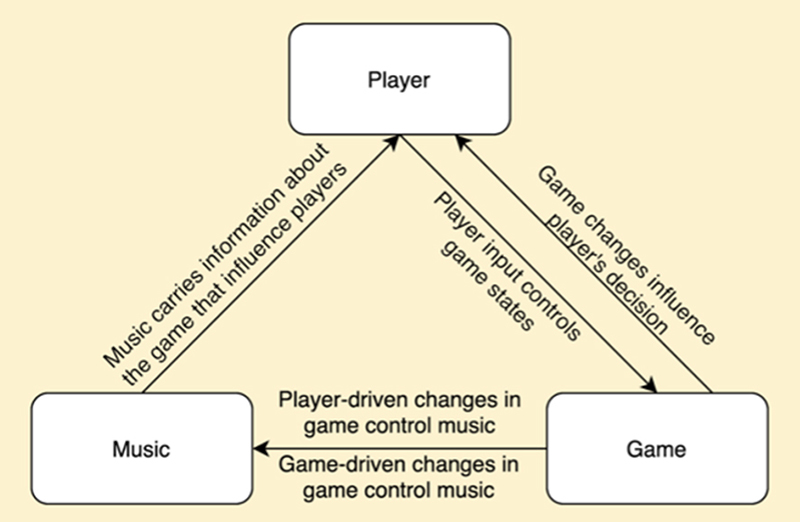

YL: Yes, that's the principle. But more specifically, in different ways the music can react to game events to a standpoint where music can be totally generative. Like a melody can be generated from game content, instead of having a pre-scored linear thing.

JCJ: Right, and I assume that game content itself is generative in some cases now.

YL: Yes, like in 3D modeling and level design, lots of aspects are now generative and some of them are player driven even.

JCJ: We've already gotten into some jargon. Maybe we should define generative for people-what does that mean? We may want to check in that we use the same definition of this. It's kind of a computer art word in some ways.

YL: Yeah, I think we are using it the same way since you mentioned computer arts. Yes, it's hard to explain. The music structure becomes modular, so it's based on modularity. When talking about generative music compared with, for instance, adaptive game music, generative music has smaller modules, which can be just a single note, so without the real-time generation, it's not going to sound like music. Adaptive music in comparison might be compiled by smaller segments of music, so you still hear some kind of material in a linear form. When it's compiled in a nonlinear form, it still can be considered as generative, but not as generative as modules on single notes.

JCJ: That makes sense. If I was to map that on to adaptive geometry, which is my universe, you would have a set of units like mountains and lakes and rivers that you can plug tile together to make a landscape. But they're each recognizable as a discrete thing. The musical equivalent is you have sequences of-I'll misuse the music terms-but a melody or time sections of music that can then be cobbled together. Whereas if it's generative in geometric terms, I think of that as the point in space with some piece of information that then causes it to create a surface and in your case that comes from the gameplay.

YL: Yes, and musical parameters do not limit it to notes or melody even. Timing is one big thing and other things like timber or polyphony. All of these structures can be manipulated in a non-linear fashion.

JCJ: In a gaming context, you actually can't anticipate what it will sound like for the user. In theory, does every user get a unique sonic experience?

YL: Absolutely. Even if I'm not using Advanced Dynamic Music (ADM), this is a part of the theoretical part of my dissertation, so I call it ADM. But even if I'm not composing this type of music for a game, it is always interactive so you can always argue that players get individualized content at all times. This video demo is a project that I did using ADM.

JCJ: What's the landscape? Has this been done? Or is this a completely new direction for music for games?

YL: There is existing theoretical research about this, as well as some actual composition. I'm trying to first make it its own theory by defining it clearly using you know different scholars’ research because it's kind of ambiguous. The other part is how I apply these principles in my composition specifically and some of the approaches that I did in my pieces are new, so I think that can be helpful as well.

JCJ: Actually, that's a great sort of segue into an important question. You started out as a musician, as a person creating music? What did you do before this program? You were making music of this type?

YL: Before I entered this program, I was playing classical piano for all my life.

JCJ: So where did your interest in generative music come from?

YL: I have always been very interested in scoring music for film, animation, and video games. I met my current advisor Mari Kimura at Juilliard and she brought me to UCI with her. I found out that UCI has such a strong Game Design department and I started to collaborate with them. I found video games are such an interesting medium and it aligns perfectly with what we are doing in ICIT.

JCJ: So you were studying at an extremely elite arts institution in music Juilliard, but that institution has no breadth in a way. It has breadth in music and in other creative fields, but it doesn't have computer science or gaming. I used to teach at an art school and there's limited opportunity to plug your work into what the scientists or the humanists are doing. You're able to do both because you have a science component in the sense that you're working with people in Informatics, but there's a humanistic aspect. You're basically doing what I understand as a media studies project. You're trying to theorize the existence of this type of this emergent type of music. But there's a key difference.

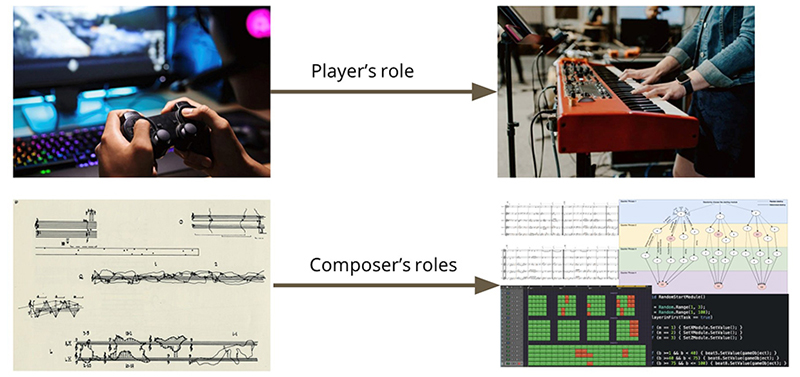

Why are you in ICIT? If you didn't know how to play, you could do all of this work in media studies. This is not to disparage media studies. Just pointing out that you don't actually have to be an expert in the technique to study what's happening. But in ICIT, you're combining the fact that you are actually a high-level musician who can compose and play music with the theory of this new genre of music that's emerging in the world of gaming. Is that a reasonable characterization of what you're doing?

YL: Yes, that sounds amazing. Thank you. It's really shocking for me. I think you are absolutely right because when I was at Juilliard, not only do they not have computer science or other arts departments and even though there is a collaboration with Columbia University, the structure is very conservative. Even for contemporary composition, like film scoring or music production, these classes are only open to composition major students and there are only six spots every year. As a non-major, I was struggling a lot. I was waitlisted for a whole year and then getting into the class. It's really different between that kind of institution and then an institution like UC Irvine or the UC system. There are so many collaborative and multidisciplinary opportunities here.

JCJ: ICIT to me is all about praxis. You are practitioners, but you are theorizing the nature of that practice. This is distinct from most other university pursuits which is basically all theoretical in some way. Experimental science is different in that its not the same thing as practice. It's exciting but also confusing to the institution how to integrate people who have actual practice experience in something as specific as music or design for that matter. Who are you working with in Informatics?

YL: Theresa Jean Tanenbaum or Tess Tanenbaum.

JCJ: She’s one of our honorary faculty fellows in the school of the arts. We do a few things with her. That's great and that's where you're getting the gaming sort of side of the puzzle?

YL: Yes, I attended a couple of her classes, as well as Global Game Jam. It's been hosted on-site at UC Irvine for three consecutive years and I have participated every time. She's the leader of that and it's really fun.

JCJ: That’s great. So you've been in the program for a number of years it sounds? How much more time do you have with us?

YL: This is my last quarter actually.

JCJ: Oh wow, congratulations!

YL: Thank you.

JCJ: In a project like yours, what does the dissertation look like? Is there a demonstration component to the dissertation? Tell us a bit about how that works in ICIT.

YL: It's a combination of original composition or creative works and a paper.

JCJ: Have you already performed the work? How do we see it?

YL: During the pandemic, I recorded the gameplay of two game projects, so that's the performance of my work. Ideally, I was hoping to have multiple players play and then each of them have different content generated in the music part. But I recorded it. This video demo is one of my dissertation projects where I experimented with generative melodies and phrasing structures, and other algorithmic music procedures.

JCJ: In the work that you do, you have to create the algorithmic programming side to be able to have the composition generate in response to game play. You've also theorized in conventional dissertation form and connected it to the broader world of algorithmic congenital music.

YL: Yeah, that's right.

JCJ: That's what's so cool about this kind of program is it insists upon a demonstration or an application. It's not to say that the research in the arts has to distinguish itself from other forms of research. But what makes this not a media studies project is that first component. You have to have both the requisite expertise to be able to produce that programming or leverage it from elsewhere, depending on if you collaborate with others.

Your project and other projects like yours speak to how algorithms can inform the creation of music. A computer scientist could also do that kind of work. But in the absence of musical training, what does music bring to the world of algorithms? Is that a two-way conversation? Describe that to us.

YL: Several articles in my bibliography talk about how to use algorithms or machine learning in music composition. I found that the generated result of the music sounds very abstract, especially for the type of algorithm that I use the Markov chain process. It doesn't convey a particular style. It’s not a complete piece. I found some theoretical analysis of the music is missing from this research because they probably do not know how to organize harmony or manage multiple melodic layers. Instead, they just create one single melodic line. This kind of conversation I think is missing from prior scientific research in algorithmic composition.

JCJ: It's easy to have a computer make sounds. It's harder to have a computer make music as we understand it. Especially as you understand it as a high level practitioner of music.

YL: Yeah, the challenge is to how to teach the computer music theory, so it allows the computer do generative work.

JCJ: In an early computer era, John Cage's conceptual work is almost anticipating algorithmic work, like creating a structure. Does that play any role in your work directly? Or is it just in the background of all generative music projects?

YL: It's definitely in the background because he has pieces where individual instruments are given a score that is mobile structured and then the conductor can manipulate and compile the piece together in a real-time scenario. That's definitely one of my inspirations when I'm doing this work. It can also track back to Mozar. He's the first composer who created music games where he created a chart of music elements. people can throw dice into this chart and whenever the dice is in a particular music segment, the musician will play that segment. That's how the whole piece is constructed.

JCJ: But are those ideas more accurately described as adaptive in that they have larger modules? Or are they actually generative?

YL: I think it depends on how fast you throw the dice.

JCJ: Right because in the Mozart game, you can throw the dice instantaneously after somebody's just gotten started and then they have to fluidly adapt to the next roll. That's great that Mozart's more sophisticated than Cage. Not surprising either. The word in “ICIT” that's the most distant from the rest of the university is the word “improvisation.” It’s almost the antithesis of science in some ways. Although, we can study improvisation. I imagine the rest of the university is kind of confused by that. How does what you're doing relate to the the whole concept and theory of improvisation? Are the computers improvising? Or is it just a really fast procedural composition?

YL: Technically, it’s the computer improvising but because everything is linked with players input data, my goal is to simulate a scenario where the player is improvising the game score, so without the player input the gate the score isn't complete.

JCJ: Is there a game where the goal of the player is to generate music? I suppose a person could hack a game and just refuse to play it. For instance, you're in World of Warcraft and you're running around and you could be indifferent to all the other activity and simply try to aesthetically maximize the nature of the score.

YL: You accept multiple missions and then it triggers the sound and you try to accept a lot of missions at once and then it becomes a short musical improvisation. That's absolutely the kind of interaction that I'm trying to create. My goal is to bring this music improvisation to every player, so they don't necessarily need any musical training to improvise the game score. Music is like painting where small bits of musical ideas are like colors on a palette. While in ADM, a composer would decide and provide a collection of available colors, the players are given the freedom to use these colors in different ways. For one of my projects, I have linked all the players controls on the joystick to particular musical parameters like controlling the voice leading, controlling which pitch is generated, which harmony is moving, etc.

JCJ: What advice would you give to yourself before you started in ICIT or as a student from Juilliard who's considering coming to UCI? What were the biggest challenges and surprises in this transition for you?

YL: This is a great question and it's very challenging. I would tell my colleagues who are working in you know the old conservatory ways of education to just be brave and get out of your comfort zone. Evaluate the importance of theoretical research whether it's linked with an interdisciplinary project or pure music theory. I found that this theoretical research is the fountain of inspiration for music creativity, which is probably not as common as their current daily training where you just repeat lot of material that you are given.

JCJ: Thank you for taking the question sincerely. If I were to paraphrase, you're saying that musicians can find inspiration and theoretical work that they might have been disregarding because they were busy practicing.

The link between the conservatory model of education and the research model or the model pursued at UCI are very different. We have all sorts of points of conflict even within the Claire Trevor School of the Arts, where the conservatory model is harder to support. What did you bring to UCI as a person steeped in conservatory training? What strength did that provide relative to a student who didn't have that training? I don't know if there are students in your program who came from B.A. programs that didn't have the depth of music training. Surely, there's an upside. The conservatory training is so hard and so relentless. How did that help you?

YL: It's related to my previous suggestion. I think I have a unique ability to translate theory into something concrete in music. I'm not exactly sure how I obtained this ability but it seems natural for me to start with something theoretical and then put it into my composition. I think my previous training has given me a lot of you know musical intuition, as well as trained my ears. I can hear certain things before I even write them. It's hard to describe, but I think it's very important.

JCJ: That makes sense to me. You're constantly able to channel everything you learn through the fact that you're intuitively attached to an instrument. There's a confidence that comes from that too. You've always got a filter that works and and then, of course, you have weaknesses. I didn't have a theoretical background and I don't know if that was challenging for you at first.

YL: Yes, it’s the same for me and I only started composing my own work around six years ago.

JCJ: Thank you so much for joining us this!